Words, and the Forging of Truth and Power

Once private, intangible thoughts enter the shared physical world through words, they become something new: banners of truth and instruments of power which people will fight over. In this essay, we figure out why.

Our inability as human beings to know all there is to know automatically predisposes us to oversimplification: we compress knowledge and beliefs into symbols we can use that stand for the whole. Nowhere is this more self-evident than with words.

Words provide us with an extraordinary bridge between the personal ‘inner world’ of our minds and our shared physical world. They enable us to convert our private, intangible thoughts into something that can be experienced by others in time and space.

But once those thoughts enter the physical realm, they become something entirely new: banners of truth and instruments of power which people will, quite literally, fight over.

In this essay, we figure out why. We begin by dissecting a ‘cat’.

But what even is a ‘cat’?

Consider a word like ‘cat’. It is a single symbol (which we call ‘a word’) that consists of three other symbols (the letters ‘c’, ‘a’, ‘t’) that allows us to differentiate it from everything that is ‘not-cat’ simply by changing one of its constituent symbols. Thus, if we change ‘c’ to ‘m’ we have a word (‘mat’) that represents something completely different from cat. Yet neither the words ‘cat’ nor ‘mat’ are the entities themselves. They are merely symbols we use as stand-ins for those entities.

When we read or hear the word cat, it triggers a collection of memories and mental associations we’ve accumulated over years. Which means that the words we use don’t even directly represent the entities they refer to. Instead they represent our own personal knowledge and beliefs about those entities.

One person hearing the word ‘cat’ may have a completely different notion of what a cat is from another person, particularly if one of them is allergic to cats (“Keep that thing away from me!”) and the other has recently lost their cherished companion (“She was everything to me”).

As broad as a cat

The word ‘cat’ is also very broad. It encompasses everything from domestic cats—together with all their different breeds—to wild cats like tigers and lynxes. We even apply it to cartoon cats like Tom (from Tom and Jerry). And as if that’s not broad enough, not only does the word symbolise every cat imaginable, it also encapsulates everything related to cats: their whiskers, eyes that ‘glow in the dark’, their legendary loathing of dogs, their sacred status amongst certain cultures etc.

Letting the cat out of box

The problem is that when we use a generic word like ‘cat’ it is simply too broad for specific purposes: what may be true for some entities we label as cat may be completely untrue for others. We can even see this with a dictionary definition. The following is taken from the Merriam-Webster definition:

1. A carnivorous mammal long domesticated as a pet and for catching rats and mice

2. Any of a family of carnivorous usually solitary and nocturnal mammals (such as the domestic cat, lion, tiger, leopard, jaguar, cougar, wildcat, lynx, and cheetah)

We don’t have to think too hard to come up with exceptions to this definition: dogs too are carnivorous mammals long domesticated as a pet, with some breeds—such as Jack Russels and Fox Terriers—even catching mice and rats. Does this make them ‘cats’? Meanwhile, lions and cheetahs can hardly be described as nocturnal or solitary. Does this mean they’re ‘not-cats’?

My ‘cat’ is truthier than your ‘cat’

Imagine asking a young child to describe what a cat is before they’d learnt that tigers can be described as cats too. They might recount their own experience of the family cat: it sits on their lap, loves a saucer of milk, purrs when stroked, uses a litter tray in the back porch, comes and goes into the house whenever it pleases.

Now imagine this child (let’s call her Annie) is describing this example of a cat (which for her typifies ALL cats) to another young child (let’s call him Bobby) who has only ever known the word ‘cat’ in the context of the lions and tigers he’s seen at the zoo where his aunt works. Both children are using the same word yet referring to completely different types of ‘cat’.

So when Annie describes her stripy family cat sitting on her lap whilst she’s trying to read, Bobby begins laughing. He’s imagining Annie’s tiny frame dwarfed by the huge bulk of a Bengal tiger. He imagines that tiger jumping up onto the kitchen table and squeezing itself impossibly through the open window.

No wonder Bobby asks her the obvious question:

“Aren’t you scared it’ll eat you? Cats are dangerous! They’ve sharp claws and huge teeth! They should be kept in cages!”

To which Annie becomes angry: the thought of anyone taking away a member of her precious family and locking them away in a cage horrifies her.

When the two children part company, Annie is convinced Bobby must be a monster who wants to hurt her family, whilst Bobby tells anyone who will listen that Annie is a liar who cannot be trusted. This juvenile clash over words will probably influence their subsequent interactions with one another, even on unrelated matters. After all, Bobby is (by nature) a monster and Annie is (by nature) a liar.

Constraining the meaning

As children gather more knowledge and experience about the world, they learn to constrain the meaning of ‘cat’ to a given context. But our default tendency to interpret words according to our own personal knowledge and beliefs never leaves us.

This should not surprise us: words don’t really represent the entity itself but rather our own mental representation of the entity. Most of the time those entities don’t even exist ‘in the real world’, at least not as the totality of our mental representation. There isn’t some ‘super-cat’ out there that possesses all the traits of every cat that ever existed or could exist (as interesting as the idea is).

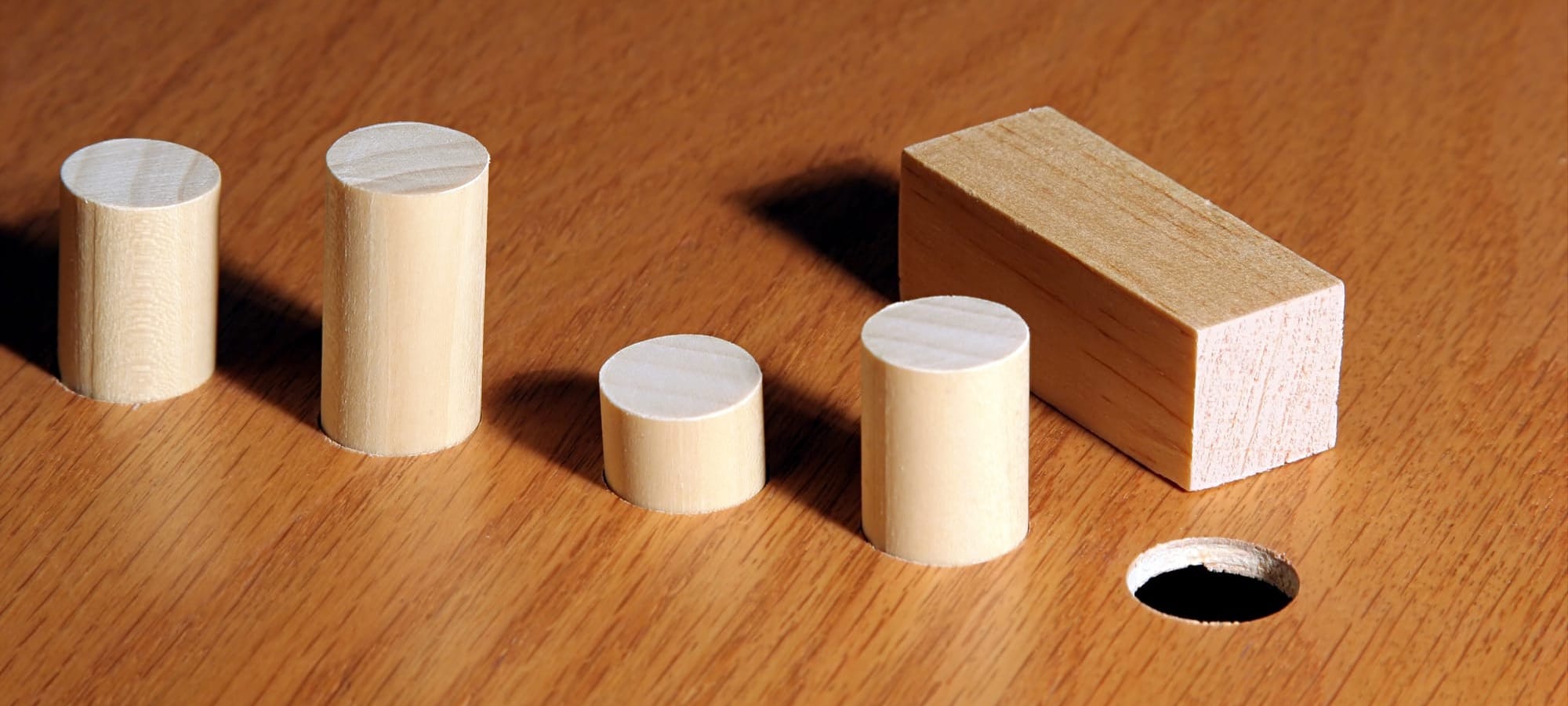

So unless the word we are using refers exclusively to a specific entity that can be differentiated from all other entities that share that word (this, not that), the word will always represent more of a fuzzy amalgamation of anything and everything we could possibly link to that word. Words will therefore normally require further context to constrain them to a specific instance: this (type of) cat, not those (types of) cats.

Same labelling, different contents

This lack of specificity immediately introduces a problem into our communication. Because our personal mental representations develop through our personal experiences and beliefs, there’s always a possibility that the word we’ve attached to our own mental representation will be exactly the same word someone else has attached to their mental representation—even though their mental representation might differ entirely from our own. The label on the packaging is the same, but the contents are very different.

We’ve already seen how problematic this can be with a seemingly straightforward word like ‘cat’. But at least ‘cat’ points to a physical entity that is widely experienced. This means lots of different people get exposed to similar examples of ‘cat’ in our shared physical world.

Over time, a word like cat therefore acquires a common meaning for a wider collection of people. It begins to take on a universal-like quality, bestowing upon it the air of ‘truth’. It then becomes easy for us to forget that the word itself is still only a symbol; a convenient shortcut that encapsulates whatever we’ve collectively chosen to put inside that package.

Yet despite the universality of its meaning, the word itself is not ‘truth’. It is not even a representation of the truth! It is merely a label we assume will overlap sufficiently with the same label attached to other people’s mental representation of ‘cat’—without needing to supply them with further context each time we use the word.

When words escape the physical realm

Words get even tricksier as we move further away from physical, specific and definable entities. Defining ‘cat’ can be hard enough due to its wide application. But at least our own mental representation of ‘cat’ will likely overlap with most other people’s when we use such a word.

But what about less concrete terms such as:

- ‘culture’

- ‘beauty’

- ‘ethnicity’

- ‘honour’

- ‘evil’

- ‘morality’

- ‘right’

- ‘intelligence’

- ‘God’

- ‘justice’

- ‘racism’

- ‘gender’

Unlike ‘cat’, these terms lack any specific physical entities we can all point to out there in the real world so it’s more difficult to guarantee a common experience and understanding when we use them with one another.

Our understanding of them may be very different from someone else’s because the mental representations they conjure up in different people’s minds no longer converge on things specific and physical. Instead they are labels we attach to intangible concepts constructed from a myriad of experiences, examples, beliefs and feelings which are, by nature, individual to us.

Expressing intangible ideas through the physical

Such mental constructions are, by default, inaccessible to anyone else unless we can somehow express those non-physical concepts in the physical world in a manner that enables another person to reconstruct our own individual mental patterns, beliefs and feelings within themselves—ideally without their own pre-conceived beliefs and feelings corrupting the process.

Consider trying to explain the word ‘love’ to someone who has never experienced it for themself. It would be easier to express what love means to you by demonstrating it, then explaining: “I do this because I love you.” Now they will have their own mental representation of the word ‘love’, constructed out of their personal experience and emotions in response to your outward expression in the physical world of an otherwise intangible concept:

- “I was (physically) cold, and you gave me (physical) shelter;

- I was (physically) hungry, and you fed me (with physical food);

- I was nobody to you, but you treated me like someone (in the physical world), expecting nothing in return.”

Removing ‘self’ from our definitions

Now imagine doing the same for a word like ‘gender’, ‘ethnicity’, ‘God’, ‘equality’ or ‘intelligence’. Observe how you personally would go about explaining to another person what those words mean.

As you do so, ask yourself:

- Are you able to separate your definition from your own experiences, feelings and beliefs?

- Do you find yourself searching for physical and specific examples (or stories) ‘out there in the real world’ that you can point to in order to back up your explanation?

- Do you find it easier to explain such terms to someone who is more like you—and therefore already more likely to think and feel the same way you do—than to someone who holds a different perspective, or grew up in a different time or place?

Doing battle over words

It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that most disagreements over words revolve around things that are less concrete. It’s always going to be those things that lack something specific and physical ‘out there’ in our shared world which we can all point to and agree upon. The more conceptual or idea-logical something is, the less consensus we’ll find (ultimately resulting in something we’ll talk about in a future article: binary coalescence).

We’ll rarely hear disagreements over the meaning of a word like ‘sunset’ or ‘rain’. By contrast, words like ‘fairness’, ‘rights’, and ‘prejudice’ are intangible concepts. What examples can we all reliably point to that won’t result in differing interpretations and opinions?

Nowhere is this potential for different perspectives more evident than the idea of ‘God’ (regardless of whether or not we personally believe).

Why religion gets the blame

Just think how frequently religion gets blamed as the root cause of major conflicts in the world. “If it wasn’t for religion…” the argument begins.

Yet it is not religion per se that results in such conflict, but rather the lack of having anything specific and physical ‘out there in our shared experience’ that everyone can universally point to and agree upon. Without this, there can never be sufficient overlap in different people’s mental representations of ‘God’.

To appreciate this, consider the following:

In the face of such a disagreement, whose ‘God’ is the ‘true God’ here? Mine or theirs? Or, if both of us are claiming to have the same God, yet we’ve both received conflicting promises, which of us has heard God more accurately or is more favoured by God?

If we ever had to conclusively settle the matter, how long before we resort to something physical to prove our own ‘rightness’?

- “Look at how God has favoured us with these (physical) natural resources and successes!”

- “Look how God always helps us (physically) defeat our enemies!”

- “Look at the evidence of our righteous (physical) deeds in comparison to theirs! Surely God is more pleased with us.”

Manufacturing some common ground

There appears to be a key principle we need to untangle here. So it might help us to break down what’s happening:

- Religion, by its very nature, obviously requires belief.

- Belief, by its very nature, is an intangible mental conception.

- Mental conceptions, by their very nature, are personal.

Which suggests that religion, by default, inherently lacks any overlap with the mental representations of others: if there was a physical explanation that everyone could agree upon, it wouldn’t be supernatural and it wouldn’t require personal belief. That’s why religion is frequently termed ‘faith’: it depends on belief without the requirement of proof.

But once faith moves from purely personal belief to collective belief, notice how often it involves something experienceable and shareable in the physical world?

- Sacred locations and buildings;

- Sacred symbolism, art and writing;

- Sacred rituals and attire;

- Collective singing, chanting or speaking;

- The recounting or re-enactment of significant events experienced by (ancestors of) the group;

- Allegory and metaphor (i.e. comparisons to the physical world, like ‘light’ and ‘darkness’).

Making the non-physical physical

These physical expressions of mental concepts serve two purposes. Firstly, they make the intangible tangible. Secondly, they provide something physical and specific that different people’s separate personal mental representations can converge upon:

- “We all pray in this direction because…”

- “We all read this text because…”

- “We all wear this item because…"

- “We all help one another because…”

It appears that the most effective collective belief systems all tend to manufacture the convergence of mental representation through tangible expressions in the physical world.

Et tu, Science?

Make no mistake here: this phenomenon of making the intangible tangible is no indication of whether the object of someone’s belief is true or not. Nor is this phenomenon of needing something physical to express the hidden or intangible unique to religion. Consider the significance of flags used by nations and social movements; or how readily we exchange mere paper or plastic notes as proxies for the gold we supposedly have stored in a bank somewhere.

Even in science, we frequently use symbols to physically express concepts and theories that would otherwise be inaccessible to us. Who can think of Darwin’s theory of evolution without immediately picturing the parade of primates progressively transforming into upright homo sapiens? Or Bohr’s famous model of electrons orbiting an atom’s nucleus like planets round a sun? Or Schrödinger’s Cat that is neither dead nor alive?

And what about that lonely polar bear marooned on a melting iceberg?

Without such physical expressions, any word we attach to an intangible concept can never be guaranteed to trigger the same mental representation as someone else’s, even though we might both be using the same word(s).

Good job I don’t believe then. Oh wait…

It turns out that this is as applicable to ‘non-believers’ as it is of ‘believers’. For how can someone say “I don’t believe in God” or “I don’t believe in climate change” unless they first possess a personal mental representation of ‘God’ or ‘climate change’ which they can subsequently reject?

Which begs the question, is the non-believer even rejecting the same concept of ‘God’ or ‘climate change’ that a believer has accepted? Maybe they have different ideas of what those words mean altogether! No wonder common ground for the intangible is so difficult to establish.

Yet despite this inherent uncertainty, we still argue over words attached to intangible mental concepts as if we were fighting for the survival of truth itself.

But whose ‘truth’ are we fighting for?

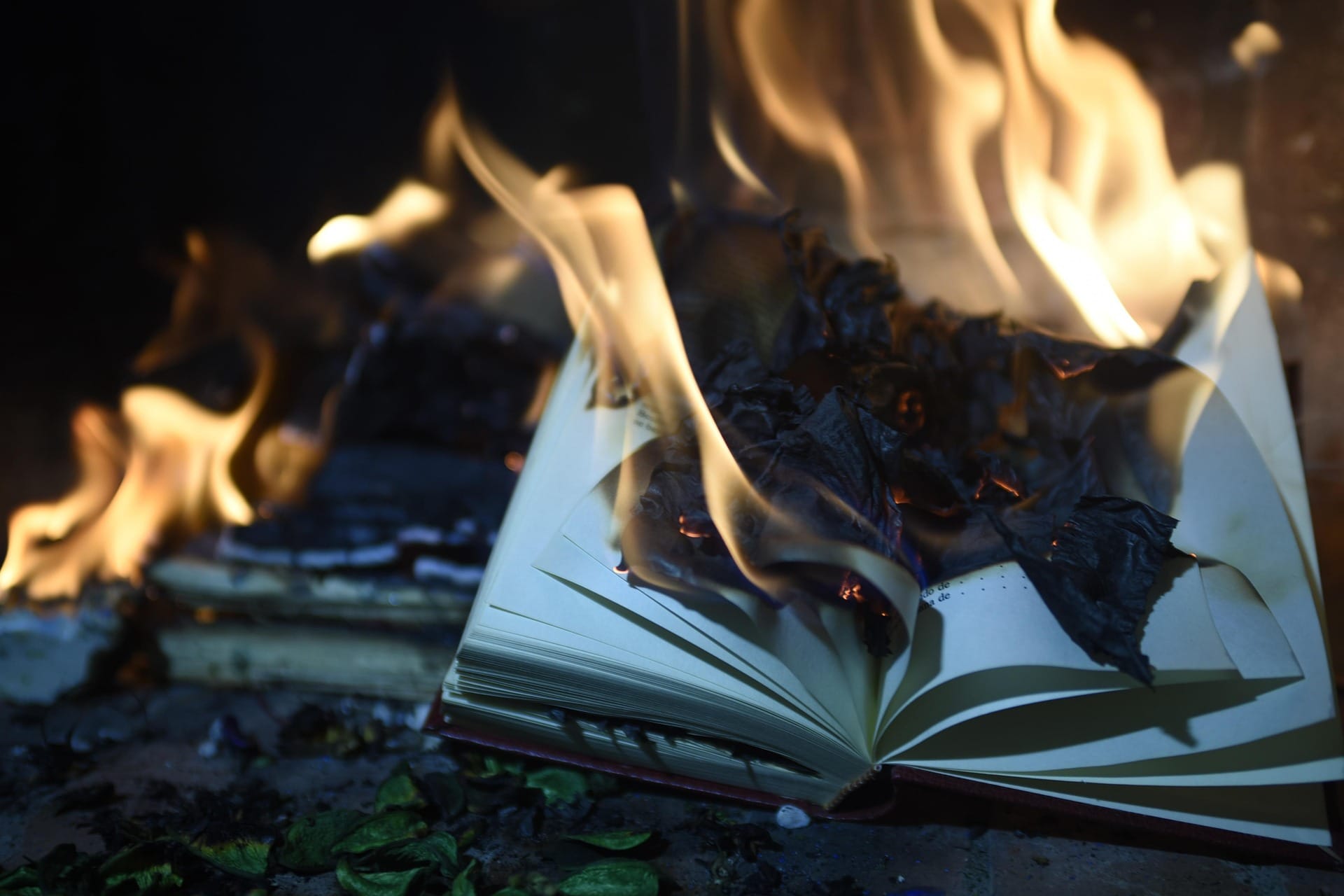

How often will someone believe it their duty to tell us we mustn’t use a certain word? If we’re lucky, we might escape with a condescending look of disapproval, but all too often using certain words will cost someone their reputation, perhaps worse. Because instead of words acting as mere proxies for mental representations, they get imbued with the status of manifest truth on earth—or else some incarnation of an evil that must be extinguished before it destroys humanity.

Consequently, how we use a word can be taken by others as indicative of our regard or disregard for whatever it is the word is understood by them to represent. How a word is treated then acquires the same significance bestowed upon the treatment of other symbols such as saluting/burning a flag or consecrating/desecrating a religious building.

The magic of words

We witness this attribution of power to words in the notion that some words are ‘taboo’, ‘not OK’, or should be proscribed as ‘blasphemy’ or ‘hate speech’. But once this notion gets converted into some mandated action—through ‘guidelines’, ‘community rules’, regulations or laws—the stage is set for an alteration in the physical realm on account of words; words that have their origin in the purely non-physical mental realm:

- “Because you used those words, you must now lose your job or source of income.” (‘cancelled’)

- “Because you used those words, you must now have your physical liberty taken away.” (‘imprisonment’)

- “Because you used those words, your physical body must now be destroyed.” (‘death’)

All it takes is a single word or phrase (apparently) and someone’s entire life can be catastrophically and irreversibly altered—irrespective of every other aspect of that person’s character, qualities and contribution to society!

It’s like magic. In speaking, we create or destroy.

A self-imposed, collective illusion

Let’s examine what’s happening here:

- Personal Belief

The process begins with someone’s personal belief that a specific word being used by another person possesses some intrinsic power (e.g. to cause ‘harm’—whether this be an ancient idea such as bringing down the wrath of the gods, or the modern notion of making people feel ‘unsafe’). - Personal Behavioural Change

This personal belief then alters their behaviour in the physical world towards the person using the word. This alteration in behaviour means the word has now acquired some transformative power in the physical world. - Observation by Third Parties

Others then observe this alteration to the physical world and note the involvement of the word. - Collective Belief

This then feeds a collective belief that the word itself possesses intrinsic power and should be treated with caution. - Imposed Behavioural Change

If sufficient people in a society believe the word possesses power, not only will those ‘believers’ alter their own behaviour, but they may then seek to impose changes in the behaviour of ‘non-believers’, convinced it is for everyone’s good.

Punishing others for our beliefs

Thus, words get imbued with a gravitas and sanctity that is nothing more than a collective, self-imposed illusion. And this despite the fact that—as we’ve already established with the example of ‘cat’—a word itself is not ‘the truth’; nor even is the mental representation that the word points to.

As a result, we can’t even be certain that the person being punished for using such a word possesses the same mental representation as the one for which they’re being punished!

After all, how can we know what someone else’s personal experiences, beliefs and feelings are that make up the mental representation they’ve currently attached to a word? Maybe they’re missing some vital information or context compared to their punishers. Maybe they possess some information or context that their self-appointed punishers don’t have.

We just don’t know.

But how can we? The only way we can know what another person thinks or feels is by letting them express themselves. And what’s the best way for someone to express themselves?

With words, the very things we’ve stopped them using.

Revealing our own beliefs by judging others

So if we punish someone for using certain words, aren’t we really just revealing what the word symbolises for us?

Are we really so self-centred that we believe everyone will (or should) automatically hold the same mental representation for a word that we do? Surely if there’s scope for variation in different people’s mental representation for a seemingly straightforward word like ‘cat’, how much more for words attached to complex issues or intangible ideas?

Concepts such as ‘God’, ‘ethnicity’, ‘gender’ and ‘fairness’ intrinsically lack something physical and specific we can all point to and universally say, “Yes, that’s what I’m talking about too!”

Which means that to understand such words requires us to aggregate many different examples over time, coupled with context and a good deal of interpretation (application of belief), so that we incrementally learn to recognise recurring patterns and relationships across those different examples. Naturally, this will result in the meaning of such words changing over time as more examples get added—across different people’s mental representations and worldviews, and according to context.

The ultimate forever war

As a consequence, any definition for words attached to intangible concepts will be intrinsically fluid, even nebulous. This means human beings will be able to argue forever over the meaning, applicability and appropriateness of such words yet never reach a collective conclusion!

Once a word gets attached to a complex idea, it will always be possible to offer counter-examples to someone else’s argument and understanding (“Yes, but what about…”), no matter which side of a debate we find ourselves on.

Being able to offer such counter-examples is not evidence that you or they have a superior argument, nor is it evidence of how right or wrong someone’s perspective is. It is simply an inevitable feature of attaching words that are constrained to a specific time, a specific space and a specific context onto ideas whose scope exceeds the limitations of specificity, time and space.

But isn’t this what we should expect?

Why words fail us

Words by their very nature are specific and defining. That’s why we have dictionaries. Yet we frequently apply words to concepts that, by their very nature, exist outside specificity and definability!

So there’s a built-in mismatch here, between words that exist in the physical realm and thoughts that exist in the non-physical realm.

Using words to convey thoughts is like trying to carry a river in a bucket or capture a person’s life in an obituary. Yes, we’ll convey some of their ‘essence’, but how much more do we discard in doing so? We’re forced by the constraints of the size of the bucket or word count of the obituary to select which parts of the river or someone’s life we personally choose to put in it.

If someone else was faced with the same task, would they capture the same essence as we would? And if they then presented us with what they’d personally selected, would we agree their snapshot ‘perfectly captured the subject’? Or would we instead protest that it’s not the river or person we know, countering with our own examples to prove how flawed the other person’s portrayal was?

Sharing the physical world: consensus or conflict

Any mental representation (and the words we attach to them) that represents something non-physical and/or dynamic will inherently struggle to establish adequate overlapping mental representations across different minds to consistently establish consensus—unless those separate minds can converge on something manifest in the physical world.

That’s why significant events from a group’s history or collective childhood prove so powerful in shaping a culture or generation.

It is only through having a shared experience in a shared physical world that our separate mental representations get to converge in time and space with other people’s. The stronger this convergence, the greater the consensus over a word’s meaning–and ‘truthiness’.

Thus:

- the more accessible something is;

- the more unique;

- the more consistent the sensory stimulus;

- the more persistent across different contexts and perspectives;

- the more spatially stable;

- the more unchanging over time,

…the greater this convergence will be.

So we find that words like ‘eat’, ‘fire’, ‘water’, ‘sun’, ‘moon’, ‘eye’, ‘hand’, and ‘stone’ will tend to be more convergent across more minds and more contexts because our shared experience of them will be similar across time and space. Such words will therefore possess a lower likelihood of misunderstanding and contention.

Transforming the world(s), one word at a time

Whenever we associate a word with something physical, specific and definable within our shared physical world, our personal mental representations will get constrained by the physical: this, not that. Thinking of ‘fire’ as something cold, for example, is very quickly rebutted by the physical world.

We could therefore say that the direction of transformation is inwards, from the ‘outer world’ (shared, physical) to our ‘inner world’ (personal, mental). It is our shared reality (‘fire hurts if we put our hands in it’) imposing itself on personal beliefs (‘fire cannot hurt me… ouch!’).

But once we venture into concepts and ideas such as:

- right/wrong

- good/evil

- justice/injustice

- equality/inequality

- God

- gender

- race and racism

- rights and responsibility

and all those other contentious subjects we spend so much time arguing over, then the direction of transformation switches.

It now moves outwards, from our ‘inner world’—the world where our personal experiences, personal beliefs, personal values reside—into the ‘outer world’, as we express those beliefs and values in the physical world through our choices, words and actions. In other words, the non-physical mental world seeks to constrain the physical world: this, not that.

It now becomes about individual personal beliefs imposing themselves on our shared reality:

- This is good, that is not

- This is just, that is not

- This is feminine, that is masculine

- This is racism, that is not racism

- This proves God exists, that proves there is no God

- This is allowable, that is not

Conclusion

Words are merely symbols that point to personal mental representations. They act as a bridge between our ‘inner world’ (private, mental) and our ’outer world’ (shared, physical).

Whenever we mistake those symbols for truth itself, it pushes us to alter the physical world to bring it into alignment with our own, personal mental representations. Here, the direction of transformation is from our inner world to the outer world:

Words gain their ‘truthiness’ through collective belief about their meaning whenever there is sufficient overlap across different people’s mental representations attached to the same word.

So when a word references something specific and experienceable in the physical world (like ‘sunset’ or ‘eye’), our separate mental representations get to converge on the same thing. The direction of transformation is from the outer world to our inner world:

But when a word gets attached to a mental concept that extends beyond the boundaries of the physically definable and/or specific, it is far less likely that different people’s separate mental representations will overlap perfectly, leaving plenty of wiggle room for different interpretations and perspectives.

Consequently, two people might use the same word to mean completely different things, yet entirely believe the other person means the exact same thing they do! If they then act on this assumption, that belief becomes physical.

Reshaping the physical world

So when two people’s physical expressions—their choices, words and actions—of their separate mental representations then prove incompatible with one another’s, that’s when people begin to “fight for truth”. In reality, they are simply trying to reshape their shared outer world in accordance with the respective mental representations they’ve each attached to the word.

This reshaping will then be carried out in accordance with the blueprint of their own inner world, which means their personal experiences, beliefs and values will be the template against which everything else gets compared.

And if their inner world and the outer world do not match? Well, that’s when a re-alignment becomes necessary.

But what should change in order to bring about this re-alignment? Should it be a person’s inner world—home of their individual experiences, beliefs and values? Or should it be the outer world—the physical realm they share with others?

On the face of it, the answer may seem obvious. But as we’ll see in the next article, there’s a massive ‘gotcha’.